Human Genome

In a pre-print paper that was featured in BioRxiv, the new results (that have yet to be peer-reviewed), claim to have found the last 8% of human DNA and if this is verified, will mean that this is the first complete human genome sequence ever created.

This has never been an easy journey. The complete human genome is made up of 3.055 billion base pairs, which means 3.055 billion individual letters that need to be identified and put in the correct spot while also getting rid of overlapping sections, and then stitched together in a very very long string.

The Human Genome Sequencing Consortium ended in 2001, after publishing their first drafts of the human genome. These results paved the way for future attempts and almost every facet of human genetics available now. The last draft of the human genome that has been used until now as a reference came out in 2013. However, drafts have always left out the most complex areas of human DNA.

Oxford Nanopore

These sequences are very repetitive and contain duplicated regions, making it very difficult to piece them together. It is almost like trying to fit puzzle pieces together that are all the same shape and don’t have images on the front. That’s how 8% of the genetic material was left out. That left scientists with the task of finding other methods that were more accurate in sequencing so they could uncover the unknown parts of the genome.

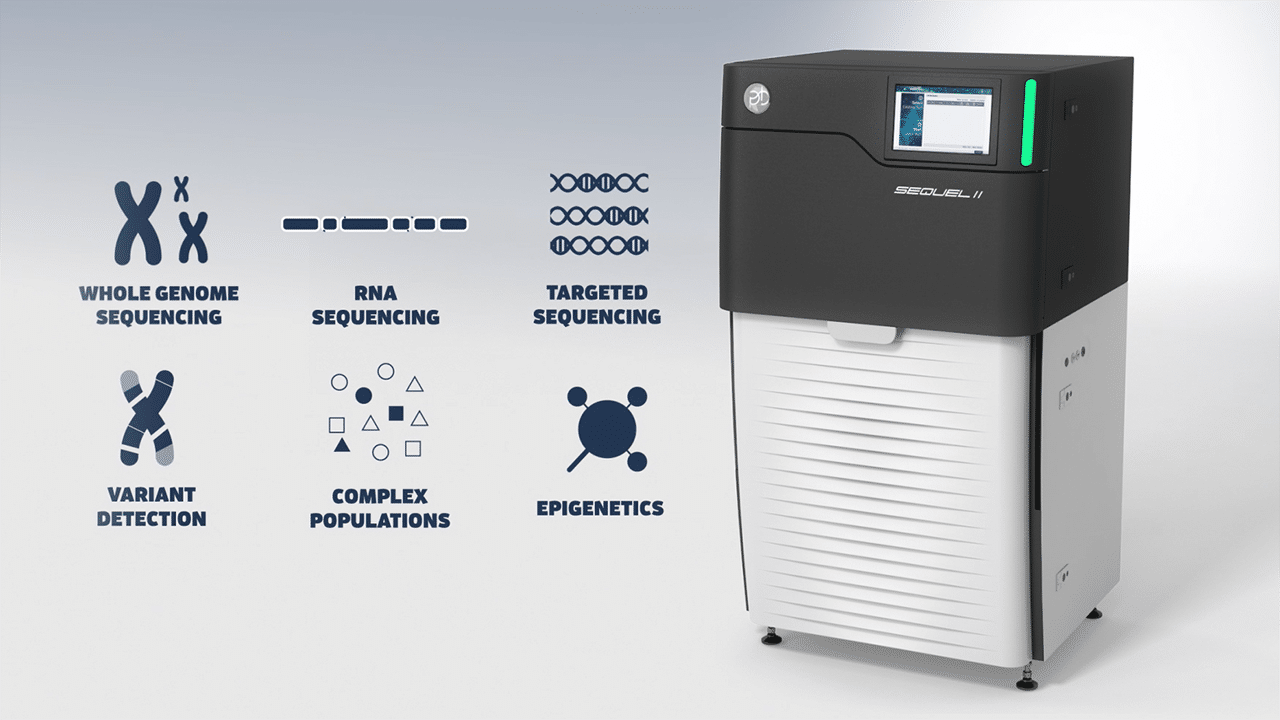

Researchers turned to two newer and more accurate techniques: PacBio HiFi ultra-long read sequencing, and Oxford Nanopore. HiFi sequencing allows long sections of DNA to be sequenced at the same time without sacrificing accuracy. Oxford Nanopore takes single strands of bases and pushes them through a tiny pore, which result in changes in the electrical current that give scientists an indication of which bae is passing through. These techniques actually complement one another, so using them in tandem helped understand the last mysterious 8%.

The T2T Consortium was able to uncover 200 million new base pairs. Within these, 2226 were genes and 115 of those were expected to code for a protein. If this paper will be peer-reviewed, it will become the biggest update in the human reference genome since it was released almost 20 years ago.

The team notes that while this appears to be the complete human genome, about 0.3% might be erroneous. It also is not a complete map of human chromosomes.

PacBio HiFi Sequencing